A new study has revived hopes for an effective vaginal

microbicide in preventing the transmission of HIV. A

compound widely used in cosmetics and foods can block

transmission of the virus by interfering with the

immunological steps to infection,

researchers report in Nature this week.

|

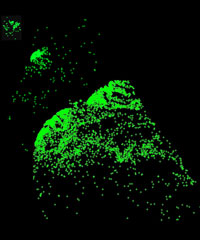

Representation of virus

expansion

after SIV exposure. Green

crosses: clusters of infected cells.

Image: A. Haase |

The compound's microbicide potential has so far been tested

in vivo only in monkeys, but in vitro results suggest it

also works against the human version of the virus.

"I think this is a really exciting study," said

Melissa Robbiani, senior scientist at the Population

Council, a New York research and policy nonprofit focused on

AIDS and reproductive health. To date, most microbicides

under development work by simply blocking the virus from

entering the body or target cells, said Robbiani, who was

not involved in the research, "whereas this is actually

targeting the immune system and modulating immune function."

With a vaccine for HIV still years away, researchers have

long pinned their hopes on a topical product that could be

applied to the vagina to stem the virus's spread. The past

few years, though, have brought dismaying results in

microbicide development. In February, 2008, a promising

microbicide gel called Carraguard

was deemed ineffective in a Phase 3 study. And the

February before that, negative results from a Phase III

trial

sank a potential microbicide called Ushercell.

Ashley

Haase at the University of Minnesota, the current

study's main author, and his colleagues began by mapping the

innate immune response initiated locally in the vagina upon

exposure to the virus. They observed growing clusters of

infected immune cells in the vaginas of monkeys exposed to

simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), the monkey version of

HIV. First, plasmacytoid dendritic cells rushed to the

scene; those spurred a chemokine and cytokine response,

which in turn brought CD4+ T cells. The T cells would then

be infected by the virus, fueling its spread throughout the

body, Haase and coauthor

Patrick Schlievert explained in a press conference

yesterday (March 3).

The team reasoned that "if you could break one of the links

in that chain, you would break the influx of target cells

that the virus needed" to infect further cells, Haase said.

They tested the compound glycerol monolaurate (GML) in that

role because other research shows it appears to block the

growth of microorganisms such as Staphylococcus and

Chlamydia, and because it was already FDA-approved for oral

and topical use. (GML, an ester, is commonly used as an

emulsifier in cosmetics and foods such as ice cream.) In

cultured human vaginal epithelial cells exposed to HIV, they

found, GML blocked the production of molecules that appear

during inflammation and that are thought to increase

susceptibility to HIV infection.

The researchers then made up a 5% GML solution dissolved in

a lubricant called KY warming gel, and applied it to five

rhesus macaques that had been vaginally exposed to SIV. The

GML gel blocked acute infection in all five of the monkeys

tested, while four out of five control moneys, exposed to

the virus in the same way, became infected. "The results, we

think, are very encouraging," said Haase in the press

conference.

The study not only demonstrated the efficacy of GML in

blocking the virulence of immunodeficiency viruses,

Robbinani noted, but it also "provided additional evidence

for the innate response role in infection" and teased out

the roles of different immune cells in propagating the

virus. "That's important just from a biology standpoint,"

she said.

Haase and Schlievert noted that further animal testing is

needed before GML can be tested in humans. One of the five

monkeys in which the gel was tested initially appeared to be

protected from SIV, but months later developed the

infection, they said; long-term studies will have to be done

to understand how often such "occult infections" occur. "And

we also need to find much better dosing schedules [that are]

more applicable to the real world," Haase said in the press

conference.

Also, they cautioned, the compound's effectiveness in

monkeys can't be extrapolated to humans. "Vaginal

transmission by rhesus macaques is regarded by many as the

best animal model for HIV transmission, but it's still an

animal model," Haas said.

Haase et al's study isn't the only positive recent news on

the microbicide front. Last month, researchers from an

international collaboration called the Microbicide Trials

Network reported

promising results from a trial of another microbicide in

development, PRO2002, a polymer intended to interfere in

interactions between HIV and its target cells. Those

findings, from a Phase II safety and efficacy study,

prompted the Gates Foundation

to pump $100 million into the International Partnership

for Microbicides, a Maryland-based organization working on

HIV microbicide development.